Table of contents I wrote down my hiring playbook and it turned out to become a book. I decided to split it in the following 3 chapters:

The Talent Machine: A predictable recruiting playbook for technical roles.

Building the pipeline: A sales-driven process for hiring.

How to scale hiring: Hire hundreds of engineers without dying

In the previous article, I argued that recruiting is just a sales process. And like any good sales process, it starts with a great product: an exceptional place to work. Now it’s time to hit the streets and start selling.

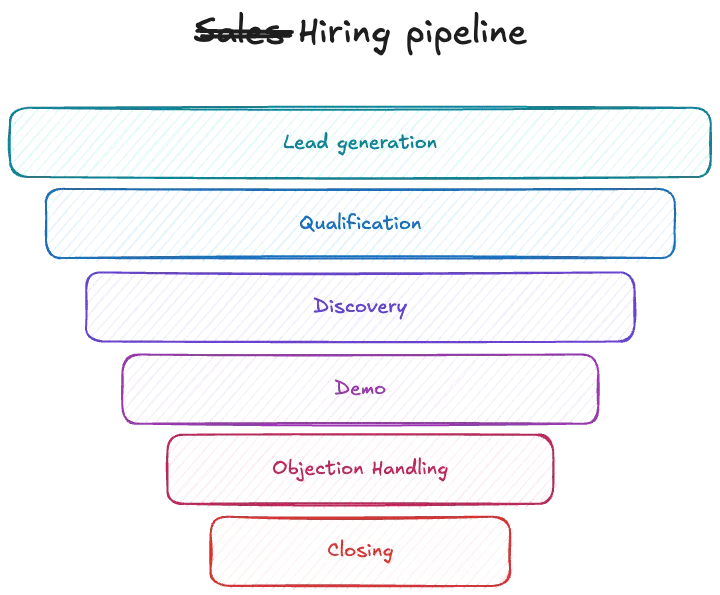

To do so, let's first understand how a sales process works:

Lead generation: Identify your ICP (Ideal Candidate Profile) and start collecting leads.

Qualification: Qualify the leads by checking if they match your ICP.

Discovery: Understand their needs and pain points.

Demo: Show them your product and how it can solve their problems.

Objection Handling: Address concerns.

Closing: Close the deal.

Most sales processes follow a similar flow, and hiring works much the same way. The key difference is that Objection Handling in hiring cuts both ways: you’re also assessing whether the candidate is a good fit. You don’t often hear a salesperson say, “Sorry, we don’t think you’d make a good customer.”

I’ll explain how to handle each of these stages. But beware, what follows is very opinionated. If it wasn’t, you wouldn’t need to read this article, just ask ChatGPT.

Lead generation

This is the most painful step of the hiring process. It's soul-crushing work, but it's the only way I know to grow your team.

There are several ways to generate leads, each with its pros and cons. You’ll start with outbound, but as you grow, you’ll be do more inbound and referral channels.

Lead generation: Outbound

Outbound means proactively reaching out to people. This is the first channel you have to master since, at the beginning, no one knows who you are. Posting jobs will only get you bots or low-quality candidates, so get good at finding and contacting people yourself.

Your main tools will be LinkedIn, GitHub, and Twitter/Bluesky. You need to develop good heuristics to identify the right candidates efficiently.

Spend a couple of hours every day sourcing candidates. You should find at least 5 per hour, so that's around 50 per week. With time, you’ll discover ways to improve that number.

Some tips are:

Use advanced search filters on GitHub. Be creative.

Find companies with your stack on LinkedIn and located in your target market. Each company has a list of employees, so you can reach out to them. This is called poaching, and you have to do it delicately. The ecosystem will resent you if you raid a company going through a tough time. And the ecosystem matter, the more benevolent you are seen, the easier things will get in the future. So, allow yourself to be slightly evil, but never an asshole.

Use Twitter/Bluesky search to find candidates discussing topics or tools relevant to you.

Go to conferences and meetups and collect people’s contact information.

Discord? A great dev.to article? A Hacker News post? Reddit threads? There are candidates everywhere. I even contact people writing code on their laptops at local cafés.

The ultimate outbound tip: look in unexpected places. Everyone targets the same talent pool: engineers from startups or big tech. There’s no alpha there. If you stay creative and open-minded, you’ll find hidden gems for a fraction of the cost. Some of the best engineers I’ve met were underrated and underpaid.

If you’re remote, explore countries with a lower cost of living but strong developer communities. If not, look at agencies or game studios that work under tough deadlines for much less than cushy startups pay.

It’s essential to use some kind of CRM to track all your leads and the companies you’re sourcing from. You can use an ATS (Applicant Tracking System), a simple spreadsheet or a no-code tool. I did most of my recruiting with Airtable, and it worked fine.

Some information you want to collect at this stage is:

Name: Real or nickname, mostly to personalize the message.

Email: Often available on GitHub; there are tools to extract them automatically but don’t spam anyone. A respectful email works far better than a LinkedIn message.

Positions: Which roles they might fit.

Created at: How long they’ve been active on your CRM.

Company: Where they currently work.

Why: Why you liked this candidate and why they might be a good fit. That’s a very important field, since you will likely separate sourcing from contacting, and you will need this information on the cold email.

Current job start date: Avoid contacting people who recently changed jobs (2+ years is a perfect threshold), but keep them on file for later.

Stage: Start with “lead” and later move them to different stages.

Source: For now, “outbound.” Later, you’ll identify which channels work best.

Assigned to: Probably yourself, but as you grow, ensure each candidate speaks to only one person from your company.

Persist this data. You’ll need it to understand what works and what doesn’t. While I don’t advocate for purely data-driven hiring (too high variance), having a reality check is always helpful. Also, as you scale, more people will join the process, and candidates will pass through multiple hands.

Lead generation: Referrals

The second most important channel is referrals. It’s low-volume but extremely efficient. You already know more about the candidate, and convincing them is much easier.

There’s always debate about whether referrals should be incentivized. On one hand, people take social risk when convincing friends to join. The better your company is, the lower that risk and people who love their job will naturally tell their friends about it. On the other hand, you don’t want to encourage people to bring in unfit candidates just for the money.

What worked for me was mild compensation. It’s a “thank you,” not a financial incentive. Enough to show appreciation, but not enough to motivate people extrinsically.

Lead generation: Inbound

Inbound is what most companies overspend on: job posts, ads, and hope. It’s inefficient, especially early on. Without brand recognition, the only thing you can do to attract candidates with Inbound is to throw money at it: buy job postings and hope for the best. Even then, you won't get the talent you want, just flood your pipeline with low quality candidates that will take away your precious time.

Use that time to do Outbound instead.

Still, having job posts on your site is useful. When you reach out to candidates, they’ll check your website and browse openings. Sometimes you’ll get lucky. Maybe someone heard you on a podcast or read an article and reaches out. Just don’t rely on it as your main hiring channel.

Lead generation: Recruiters

This is where I piss off a whole industry and burn some bridges.

Don’t use external recruiters,

If you do, hire them,

mostly one.

Companies spend absurd amounts on external recruiters, often 10–25% of a candidate’s salary. Their incentives are rarely aligned with yours.

That said, you might eventually need recruiters: seasonal peaks, pivots, or roles you’ve never hired before. Just don’t rely on them too much. They’re like drugs and paid advertising: magic at first, but hard to party without them on the long run.

If you do want to use recruiters, start with several in parallel (they’ll ask for exclusivity; negotiate that). Later, hire the one who performs best. One is enough. And they should report to you, not HR. Otherwise, you’ll have someone whose performance is judged by another department, and that’s a recipe for disaster.

In my opinion, recruiters should only handle outbound sourcing. Some companies let them do first contacts or screenings, but that’s a mistake. The first call is crucial and should be done by a technical person. Engineers prefer speaking to peers, not recruiters who confuse Java with JavaScript. Screening is delicate, and we’ll discuss it later. Always have a technical person do it.

A note on HR from someone who built HR software Some companies give HR veto power in the final stage. Don’t do that. It’s your hiring process, and you must own it. For good and bad.

If HR wants to get involved, sit with them and explain the process and the decision making criteria. Let them give input and help you improve the process, but if you don't have 100% control over it, they will slow things down and lower your chances of hiring the best candidates.

Qualification

Great, you now have leads and are ready to qualify them.

This process differs slightly depending on the channel – let's delve into it (not written by an LLM, I'm just teasing you).

Qualification: Outbound

You’ve spent a week sourcing and now have 50 leads. Time to reach out. If possible, contact them via email. If not, try Twitter/Bluesky DMs, then LinkedIn. From most personal to most professional.

Craft a banger message. The title should be direct, and the body should feel personal and unique for each candidate.

My go-to structure:

Title: Simple, human, and direct. If you have a good title (CTO, VP of Engineering), show it off. Let them know you’re not a recruiter. What works best for me is something like:

“Hi, I’m the [your title] of [company name], and I want you to join us.”

Body

Who you are and what the company does: A brief, clear intro and a pitch that works.

Why you’re reaching out: Be genuine and flattering. Mention what caught your eye, their OSS project, experience, or work you admire. This is a personalized message and hopefully you had it saved on your CRM.

Why you’re hiring: Explain why the role exists and its expected impact.

Your product: Describe what working at your company feels like. If you sourced right, it will resonate.

Link to your calendar: Invite them to chat. Make it sound casual, not like an interview.

Link to your Employee Handbook: The mic drop. This document explains everything they need to know about working with you. Candidates who say “hell yeah” will save you time, and those who decline save even more.

Writing well is important. You have 2 seconds to grab their attention, so you better get better at this. I recommend newsletters like marketing examples to get better at copy. A good message can get around a 15% response rate. From 50 sourced candidates, that’s about seven qualified leads per week, not bad!

Qualification: Inbound & Referrals

Less exciting but necessary. Define your criteria and process, then go through your ATS or CRM. Discard those who clearly don’t fit, and send the rest a calendar link.

If someone isn’t right for a current role but could fit later, keep them. Build a future pipeline.

Discovery & Demo

I like to bundle discovery and demo into a single step: the first interview.

First rule: don’t call it an interview. It’s a chat. If you’re meeting in person, have a coffee or beer, but not in the office.

This keeps it personal, not transactional. You want the candidate to open up.

The goal is twofold:

Understand who they are and what they want in life.

Show them how your company fits that vision.

That order matters.

Gather information first to personalize your pitch. Are they aiming to be a CTO in five years? Great. Show them that path.

Make them comfortable. For instance, I try to make candidates laugh in the first two minutes. Be clumsy, be human. Like Dr. Slump’s Senbei Norimaki, you can get serious later.

Ask open ended questions and let them do the talk. When they open a box, dig deeper. When they don't, try mirroring (repeat what they last said).

Me: So, how is work nowadays?

Candidate: It's ok. <crickets, he is not going to expand... time to mirror>

Me: It's ok?

Candidate: Yeah. Good salary, and the manager is ok.

Me: What do you mean the manager is ok?

Candidate: You know, I had non-technical managers who just asked “how’s the project going?” I want someone technical who can help me grow.

Me: Yeah, I've seen that too. How does he help you grow? What does grow even mean?

This is great, now we are getting to an interesting place and the candidate is feeling more comfortable and willing to share. Mirroring works wonders.

Don’t rush to reject quiet candidates (some recruiters or HR people will). Some are bad at interviewing but brilliant at work. They’re undervalued by the market and often the best hires.

For getting information out of interviews I highly recommend reading Never split the difference by Chris Voss. Yes, I know. The book is about negotiation with terrorists, but the principles are similar: building trust so the conversation can lead to a positive outcome for both parties.

You can also sprinkle the conversation with some open ended questions that help complete the picture. Remember: you are not evaluating, you are discovering who you have in front of you. Experiment and write down what questions that work best for you.

Here are some that I’ve used in the past:

What's something you don't want to do?

If you could write your perfect job description, what would it be?

What makes you happy, angry, or sad?

What rabbit holes have you chased recently? Why?

If you didn’t have to work anymore, what would you do?

The second part of the chat flips the roles: you talk, they listen. Be charming, be honest, and remember that not everyone will like you, and that’s fine. It’s a numbers game.

The goal is for them to leave thinking, “Hell yeah, I want to join tomorrow.” Most companies get this backward. They drag candidates through hoops, then try to excite them at the end. You must excite them early because candidates never do your process alone.

Once someone starts interviewing with you, they’re also interviewing elsewhere. If you win their excitement and move fast, you’ll likely win them and shorten the time to hire. That's the main difference between buying and selling.

During this second half of the interview I recommend you to cover the following points:

Why the company exist

The product and the market

The company’s story and your background

Your financial situation. Be honest. This matters to a lot of engineers. Are you profitable? Say it loud, they will love that. Did you just raise a round? Mention it. Are you running out of money? I'm sorry about it, but also mention it. They will figure out sooner or later, and you would rather have them not join than leave in 1 week and waste your precious recruiting efforts.

The team

The culture

Review together the Employee Handbook so there are no questions or surprises. Talk about the employee lifecycle, the company cadence and whatnot.

If done correctly, the only thing left is for you to discover whether you want to work with them or not (buying). This means that salary is agreed at this point, not after the last interview. This is very important. There is nothing worse than spending countless hours to lose the candidate on the last step. And is not fair for the candidate either. Don't delay it. If you don’t like talking about money, rip it off. After all, you already know the price tag.

If the candidate is stronger or weaker than expected, adjust by offering a higher or lower position, not by haggling salary. People hate salary negotiation but are fine negotiating roles.

Wrap up by thanking them and asking if they’d like to start the process (remember, this was not an interview). If you’ve done well, they’ll say, “Let’s fucking go.” Then schedule the technical interview.

If your company is genuinely appealing, you should convert around 80% of these. From 7 qualified leads, you’ll get 5 interviews. If not, improve your pitch.

Objection handling

Now comes what you’re probably already doing: interviewing candidates. It’s time to figure out whether this person is really a good fit for the position or not.

My advice is to keep it simple and short. That’s it. The rest is fluff.

In my experience, and other companies confirm this, each interview has diminishing returns. During the first one, you get most of the information you need; in the following ones, not so much. Every extra interview decreases your chances of closing the candidate. Remember, you are competing against other companies, and whoever lands an offer first has an edge.

False positives and negatives are inevitable, no matter how much you interview. If you believe that talent follows a fat-tailed distribution (I do), your strategy should be to minimize false negatives. The ones who get away. Passing on a future Jeff Dean is worse than hiring someone who doesn’t work out. Your team, like most investment portfolios, will end up following a Pareto distribution. A very small set of engineers will be responsible for the majority of the company's success.

This doesn’t mean you should only hire staff+ engineers and ignore everyone else. It means you should evaluate candidates not for what they know but for what they can learn. Knowledge is easy, and getting easier by the day. But creative, curious minds are scarce.

Unfortunately, most interviews still test knowledge. Candidates can easily master the interview process, the same way LLMs cheat by engulfing all benchmark data.

What are you really testing by having a candidate solve an algorithm or data structure problem? That they’ve practiced “Mastering the Job Interview”? It’s as absurd as IQ testing, which mostly predicts how good someone is at taking IQ tests.

The best interviews are conversational. They’re hard to fake, and if you ask the right questions, you’ll learn everything you need to learn in just one interview. If you don’t believe me, listen to how Tyler Cowen interviews people, and notice how they crumble under intellectual pressure.

In these conversations, you can see how candidates reason, linearize complex thoughts, and connect or create ideas in real time. Tease them with humor. I’ve never seen an LLM make me laugh, and humor is a better proxy for intelligence than logic puzzles.

When you’re in front of a brilliant mind, it’s a fantastic experience. But it’s not quantifiable: it’s an “I know it when I see it” kind of thing. There’s no scorecard for a great conversation, and your gut will be right about 90% of the time. That’s a fantastic error rate you won’t improve no matter how many tests you make the candidate endure.

How is that interview structured? It's just talking? Isn't this "too easy"? Hold your horses! First of all, difficulty doesn’t lower error rates; it just builds exclusivity theater. And no, it's not just talking: You ask the candidate to bring code they've wrote. It can be an open source, a side project, or a take-home exercise they wrote for another company. At some point, I got to know most companies’ homework assignments in Barcelona. They weren’t very good.

Candidates love this approach. As I mentioned earlier, they’re usually interviewing with several companies, trying to maximize their chances of success. Skipping the take-home exercise is a massive speed-bump for both sides.

Assemble a team of 2 or 3 engineers to interview the candidate (yourself included if you are part of this hiring process). Usually 2 senior+ and 1 junior/mid that is mostly shadowing and learning how to interview. Spend 1 to 2 hours with each candidate. For manager roles or staff+ positions you might want to have a second interview to touch on different topics with more depth.

If the code they bring is not that interesting, then just ask open ended questions. Those shouldn't have a correct answer, like most things in life. They need to be juicy and have different levels of depth, like most things in life(2).

Some questions that I've used in the past:

Role play. the CEO storms in, stressed because customers are complaining the app is down. What do you do? Whatever they say, dig deeper. If it’s a senior role, the root cause should be something gnarly: Postgres wraparound IDs, a rogue Bitcoin miner, or maybe a solar flare flipping a bit.

You’re hired, and your first task is to add search. What do you do? This opens discussions about databases, synchronization, change data capture, and search algorithms.

How would you architect a real-time game? Why is it different from a traditional SPA? This explores distributed systems and state synchronization.

Tell me about a time where you made a technical decision that had a meaningful business impact. Oh boy, do they trip over this one.

Tell me of your biggest fuckup. What did you learn from it?

That’s it. You have a conversation, review the code, and follow your instinct. If you feel good about the candidate, make an offer.

The % of people that pass this process will largely depend on your risk aversion and how well have you sourced and done the first interview. You’ll usually see 20–50% of candidates pass. Lower than that means too strict; higher means too lenient. But take those numbers with a grain of salt. The sample sizes are small, and you’ll have lucky and unlucky streaks.

From the previous 5 candidates, this should leave you around 2 candidates to make an offer to. Getting there! Are you excited? Let's go!

Closing

The final step is to make an offer. You need a badass template ready with all the details and a deadline. A deadline? Don’t engineers hate deadlines?

Yes, they do. But job offers without deadlines suck for everyone. Here’s how things usually go wrong: you send an offer, freeze the position because you don’t want to be an asshole, and the candidate goes silent. One week passes, then two, then three. Suddenly, they tell you they’ve accepted another offer from a slower process than yours.

Bummer.

You’re now three weeks behind schedule. Sure, you could keep interviewing candidates instead of freezing the position, but that’s even worse for the candidate, who might have already told their current employer they’re leaving.

The solution is simple: set a deadline and be transparent about it. Tell them, “I’ll freeze this position for you for one week. After that, I’ll continue hiring for it.”

It’s fair for both parties. Everyone has time to think and decide, and the consequences are clear.

More importantly, a deadline creates urgency, and urgency triggers emotion. If you’ve done the first interview well, the candidate will be excited enough to overcome the fear of leaving their safe job or finishing other interview processes.

Track how long it takes from first contact to offer. Your close rate is inversely proportional to your time to hire. A realistic, excellent time to offer is two weeks.

The offer stage should have one of the highest close rates in the entire process since all details have already been discussed and agreed on. At this point, it’s just a final decision. A good close rate is around 80–90%.

That means from your last two candidates, at least one will accept.

The Talent Machine

I wrote down my hiring playbook and it turned out to be massive. I decided to split it in the following 3 chapters: The Talent Machine: A predictable recruiting playbook for technical roles. Building the pipeline: A sales-driven process for hiring Hiring Scaling: Hire hundreds of engineers without dying The room is packed. Mostly men in their 30s, wearing swag t-shirts and jeans. I'm on stage giving it all, explaining how I helped build a unicorn in Spain, an unusual creature for the local fauna. I never rehearse my talks. Like a large language model, I generate one token at a time, hoping each will lead to something the audience wants to hear. When it works, it's magic and I feel like a genius. When it doesn't, I look like a complete idiot. A successful idiot, though, since I'm the one standing on stage. This time around, they nod, laugh, and even clap at the end. I delivered. "Any questions?" I ask. My hands get a bit sweaty but it’s always the same question, and I’m ready for it: "How do you hire engineers? It's so hard." Hiring Engineers is a sales job The best engineers don’t apply for jobs. They join people who make them believe. So stop waiting, and go sell. No one – I made it up There are two ways to approach hiring: Buying talent. Selling positions. They sound similar but they are actually the opposite. Companies with a buying mindset typically throw money at the problem. They hire a team of recruiters, pay for job board postings, and optimize for filtering. In contrast, companies with a selling mindset spend time defining roles as products and positioning them in the market. They proactively look for candidates and engage them in what is, essentially, just a sales process. The emphasis shifts from weeding out “bad” candidates to convincing great ones. For the rest of this article, I will outline my sales-based recruiting playbook, the one I used to scale a team to 150 engineers in 3 years with only one recruiter. What follows might not all apply to you, but you might learn a thing or two. Product and Positioning To find a unique position, you must ignore conventional logic. Conventional logic says you find your concept inside yourself or inside the product. Not true. What you must do is look inside the prospect’s mind. Al Ries – Positioning: The battle for your mind The first thing you need to decide is what product you can sell to candidates. This "product" is the overlap between what you need and what candidates want . Essentially, you're defining your value proposition as an employer and it will drive everything else you do. Ask yourself some key questions about the opportunity you're offering: Depth vs. Breadth: Is your engineering work deep (specialized, fewer engineers needed) or shallow (broad, many generalists needed)? Location: Where is your team based? Is it in a tech hub or a more remote location? Remote Work: What is your stance on remote or hybrid work? Diversity & Inclusion: How do you approach building a diverse and inclusive team? Work Culture: Do you prioritize work-life balance, or are you a fast-paced mission-driven culture? Mission & Impact: Do you have a powerful mission or compelling problem that will inspire candidates? Technology Stack: What does your tech stack look like? Modern and exciting, or stable and boring (be honest)? Reputation: Are you a known leader in your market? Founder/Team: Who are the people behind the company and why are they exciting to work with? Compensation: How much can you realistically pay (both salary and other benefits)? Each of these questions helps define the market you're addressing and sets realistic expectations for your talent pool. Be brutally honest here about what you can offer and where you fall short. If your product is a B2B tool for accountants on a COBOL codebase and you're based in Tbilisi (not exactly a tech magnet), you might need to offer remote work or other perks to expand your reach. On the other hand, if you're curing cancer, working a 4-day week or pay the highest salaries, you can probably get away with murder (figuratively speaking). People on suits looking at a mainframeAs tempting as it is, don’t chase the largest talent pool for the sake of it. Everyone else already does. Instead, look for under-served pockets of talent, groups that match your company’s values or needs but aren’t being courted aggressively. For example, you could default to mainstream stacks like JavaScript or Python because they have the most developers. But that also means more companies looking for the same candidates. Choosing a more niche technology (say Elixir or Clojure) can narrow the pool but also the competition. You’ll find engineers who are more passionate, loyal, and easier to hire because fewer companies are after them. At Factorial, the company I founded, I applied the same idea. Most startups were obsessed with hiring 20-something engineers who’d stay late playing ping-pong and drinking beers. I was in my 30s, starting a family, and didn’t want that lifestyle anymore, so I turned it into a hiring advantage. I targeted experienced engineers in their 30s and 40s who wanted stability, flexibility, and purpose. All my messaging, from the cold emails to the interviews would revolve about that positioning, and it paid off: we attracted senior talent early and built a mature, highly productive team very fast. beer bottles on top of a ping pong tableOnce you understand what you can sell and who your market is, write it all down in a Employee Handbook. This is a public doc you’ll share with candidates. It should clearly articulate everything about working at your company. The goal is for the right people to read it and think, "Yeah, this company is for me." Conversely, if someone reads it and thinks "Nope, not my vibe", that's actually good: you've just saved everyone’s time by filtering out a poor fit early. Compensation One of the most important parts of positioning your "product" is pricing it correctly. And correctly means setting compensation such that you can attract the talent you need without running out of money. Engineers will likely be one of the biggest expenses for your company, so you must understand how many engineers you actually need and how much you can afford to pay them. If you're a bootstrapped company, you will know. But if you're VC-funded, be careful: $5M in the bank might look like infinite runway, but at $150k per engineer, that's only 11 engineers for 3 years. Once you are confident with the numbers, I highly recommend publishing the salary ranges for each role in your Employee Handbook. In fact, I go a step further: Fixed salaries per level, not ranges. Create a dual-track ladder (one for individual contributors, one for managers) with clear levels and a fixed salary at each level, alongside a rubric of what each level means. But wait, wasn’t the Employee Handbook public? Yes! Having a public document that you can share publicly massively increases your chances of hiring top talent. Candidates will often find a public salary table more fair, even if your numbers are a bit lower than what they could get elsewhere, simply because it's transparent and applies to everyone. Engineers, raised in open-source culture, thrive on transparency and clarity. If you are not clear, or hide information, they will assume you are just bullshitting. A bull, a pile of shit and a detectorFixed salaries (no negotiation, no ranges) are a bit unconventional, but in my experience it’s a net positive: No Negotiation Dance: Ranges invite negotiation, and many engineers dislike the salary negotiation process. They feel dirty talking about money, like a mercenary instead of a craftsman. By offering a fixed number, you spare candidates the stress and uncertainty. Internal Equity: Ranges create pay disparities among peers that can breed resentment. If two engineers perform the same role but one managed to haggle for $5K more, you'll eventually have tension (especially as teams grow and people talk). Perceived Fairness: A single number feels less arbitrary than a range. Candidates know exactly where they stand and what the offer is, which many find refreshingly predictable and fair. Simplicity: It streamlines the process. You can discuss comp very early and easily (more on that later) since there's a single figure on the table. Downsides? Sure, a fixed scheme means you might lose a great candidate who has a higher expectation for that level, since you’re not negotiating. That lack of flexibility can seem like a disadvantage. However, I view it differently: if your fixed salaries are truly too low to close good candidates, the answer is not ad-hoc negotiation, it's to raise your salary bands for everyone. In other words, if you’re consistently losing hires due to comp, adjust the fixed numbers upward for that role. But if you’ve done your homework on market rates and you're paying enough (you should!), then money usually won’t be the problem. By removing room for negotiation, you also remove excuses like "we have to pay more to close this hire," which forces everyone to focus on the non-monetary value your company offers. The “trimodal” nature of software Engineering Salaries Software engineering compensation has splintered into three distinct tiers in many markets. Tier 1 represents local companies or startups paying local-market rates, Tier 2 includes well-funded or mid-size companies paying above local averages, and Tier 3 is Big Tech and top-tier firms paying globally competitive packages. Gergely Orosz – The Pragmatic Engineer A few years ago, Gergely Orosz famously described how software engineer salaries in Europe had split into a trimodal distribution. They are no longer one bell curve, but three separate peaks for three categories of companies. Tier 1: Companies that pay around local market average (often non-tech companies or smaller startups). In the Netherlands, this was something like €50-75K for a senior. Tier 2: Companies that pay above local average, competing for talent in-region (e.g. well-funded scale-ups, certain mid-sized tech companies). Senior engineer comp might be €75-125K in that. Tier 3: Big Tech and international firms that pay globally competitive rates, often 2-3x what Tier 1 offers (senior packages €125-250K+ in Europe). These are the Googles, Facebooks, Ubers, high-frequency trading firms, etc., who benchmark pay worldwide. Why does this matter in our context? It’s useful for calibrating your hiring strategy. If you're a Tier 3 company (printing money or have SoftBank on your board), you can chase top 1% (p99) talent with huge offers. But most of us are not in that position. And frankly, if you’re targeting the top 10% (p90) engineers, it doesn’t really matter whether they come from a Tier 1 or Tier 2 company. In my anecdotal experience (don’t be offended, this is just my observation), Tier 3 companies do have some of the absolute best engineers, but on average have the same talent density as the other Tiers. Their sheer size and attractive brand mean they hire a lot of people, not all of whom are geniuses. Talent distribution over salary tiersSo unless you’re able to back a truck of cash up to someone's house, your chances of poaching top talent from Google/Facebook/etc. are rather slim. You’re better off finding excellent engineers in Tier 1 and Tier 2 companies who are perhaps undervalued or looking for a change. Many of the most skilled engineers I’ve hired were “undiscovered” talent at lesser-known companies. Be open-minded and look where no one else is looking. Always be searching for alpha in the hiring market. Employee lifecycle Lastly, as part of your product, you should document the employee lifecycle at your company. From start, to finish. A person considering joining you wants to know what to expect and they will love the transparency effort. In your Employee Handbook, cover topics such as: Hiring process: How many interviews will there be, and who conducts them? What skills or qualities are you evaluating at each step? Post-interview: What happens after the interviews? How quickly can candidates expect feedback or a decision? Onboarding: What does the first week/30 days/90 days look like for a new hire? What support do you provide to get them up to speed? Career progression: How do promotions work at your company? What are the expectations for each level or title, and how can one progress? (This often ties into that dual-track framework you created for salaries.) Cadence and culture: What is the rhythm of work? For example, describe the typical company cadence: yearly planning, quarterly goals, monthly all-hands, weekly team rituals, daily stand-ups, etc. Give candidates a sense of the day-to-day and the overall tempo. Writing all this out for the first time can feel overwhelming. Don’t worry. It doesn’t have to be perfect. The Employee Handbook is a living document and you'll update it as you learn and grow. But trust me, the upfront effort is worth it. All these details and clarity will save you so much time in the long run. Hiring (and then potentially losing people due to wrong expectations) is far more time-consuming and costly than writing a document. Look for inspiration and read how other companies are doing things. Steal, copy, modify, twist and shout. And do it again, until you find your message and voice. Here are some examples and resources: List of public career frameworks List of company handbooks That’s all for today. The next article is massive, and it explains in excruciating detail the whole recruiting pipeline. Please subscribe to get updates on your email!

Antimemetics

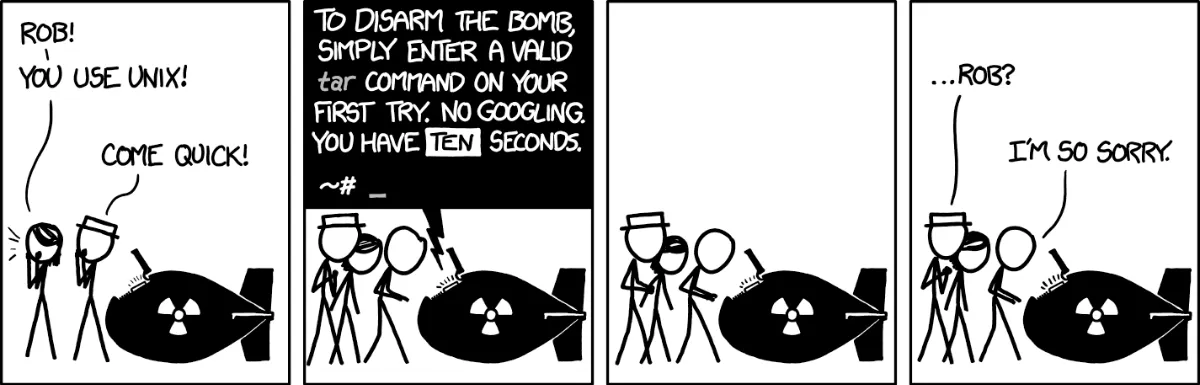

One of Charlie Munger’s most powerful mental models is to “Invert, always invert.” This book does exactly that by exploring the antithesis of memes: antimemes. These are ideas that, instead of spreading easily, fail to be retained. Individually or collectively. I’m only halfway through this book, but I can already recommend it. It’s packed with fascinating concepts that make your brain bubble and sizzle. It touches topics that feel very close to fika: building an alternative to the hostile and chaotic meme overloaded internet. xkcd tar bombIn a world where the Wario/Mario dichotomy exists, I can’t help but feel it was a missed opportunity to call them Wemes. But that’s not on the author: the name comes from the novel There Is No Antimemetics Division.

- book

- antimemetics